Lowell Lab

We are located in Beth Israel Deaconess Medical Center (7th floor, Center for Life Science Building, 3 Blackfan Street, Boston)

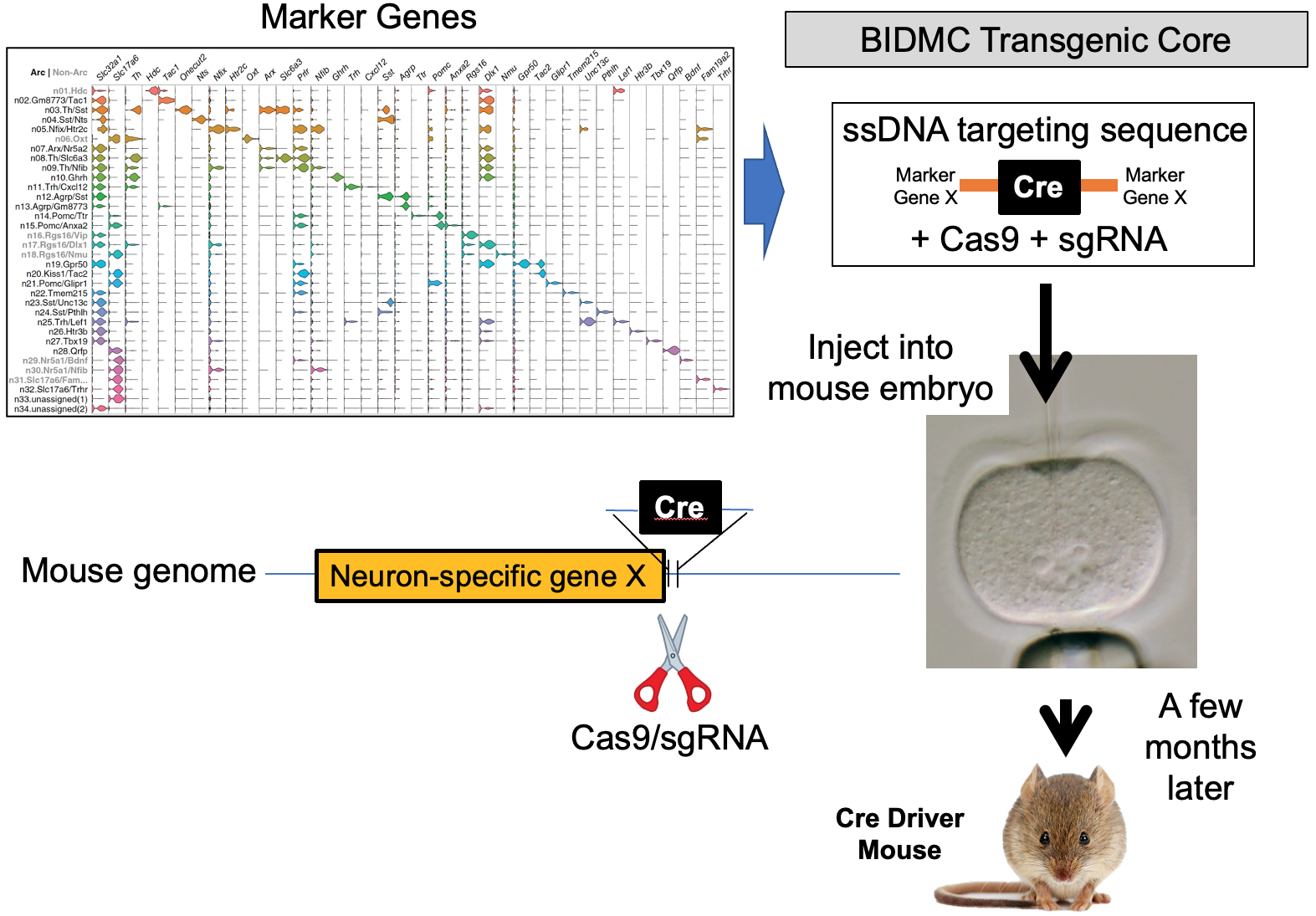

Our lab seeks to identify the neural mechanisms responsible for brain control of homeostatic drives (e.g. hunger), the autonomic nervous system, neuroendocrine systems, hormones and metabolism. To achieve this, for genetically-defined neurons of interest, we interrogate their input/output connectivity, regulation and function. This is done by combining genetically engineered mice that express, in a neuron-specific fashion, DNA recombinases (Cre, Flp, etc.) with AAVs or mice that express, in a recombinase-dependent fashion, a panel of “neuroscience tools”. Using this approach, for any given genetically-defined neuron we can: a) manipulate its firing rate to determine its role in regulating behavior and physiology, b) measure its activity in vivo to establish how that neuron responds to discrete sensory, behavioral and physiologic stimuli, and c) map its synaptic connectivity with upstream and downstream neurons to uncover the neural “wiring diagram” within which it is embedded. This information is then used to construct mechanistic models of how the brain controls physiology and behavior. Specific techniques utilized include: single neuron and spatial transcriptomics to obtain the neuronal parts list for regions of interest, mouse genetic engineering to create marker gene-recombinase mice which make possible neuron-specific expression of “neuroscience tools”, optogenetics, chemogenetics, rabies monosynaptic afferent mapping, ChR2-assisted circuit mapping, electrophysiology and in vivo assessments of neuronal activity.

OVERVIEW - CURRENT RESEARCH AREAS:

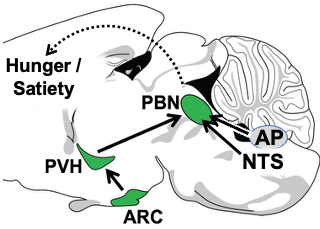

1. The Arcuate Nucleus (ARC) (AgRP and POMC neurons) —> Paraventricular Hypothalamus (PVH) (Mc4r neuron) —> Parabrachial Nucleus (PBN) non-aversive satiety circuit. Since obesity is prevalent and adversely affects health, there is great interest in understanding how the brain controls hunger/satiety. Recently, remarkable progress has been made, particularly in the discovery of the key roles played by proximal (upstream) neural circuitries in controlling hunger/satiety. These proximal circuits include the hypothalamic arcuate (ARC) (AgRP and POMC neuron) —> paraventricular (PVH) (Mc4r neuron) —> PBN circuit (a major focus of the Lowell Lab) as well as hindbrain circuits emanating from the nucleus of the solitary tract (NTS) and area postrema (AP). Despite this progress, little is known about how these proximal circuits actually affect the desire to eat. This is due to a lack of knowledge regarding how these proximal circuits engage the “higher” mesocorticolimbic structures that are, in the end, responsible for regulating the motivation to eat. Solving this has been challenging because these proximal circuits don’t directly engage these “higher” sites; instead, they do so indirectly via relays that are opaque. The lack of knowledge about these relays and how/where they route this information is one of the greatest barriers to progress. Our central premise is that the parabrachial nucleus (PBN), in its role as the principal routing hub for interoceptive information, provides this “missing” link – connecting proximal ARC —> PVH and NTS/AP satiety circuits to higher brain sites that regulate the desire to eat. Of relevance, the proximal hunger/satiety circuitries all project to and activate PBN neurons, and, importantly, the new effective Glp1r anti-obesity drugs similarly activate many PBN neurons. The main roadblocks to understanding the “routing” of hunger/satiety information by the PBN are: a) The PBN receives and routes numerous modalities of interoceptive information, many of which are unrelated to hunger/satiety - this creates a daunting “needle in the haystack” problem, and b) the field has lacked a transcriptionally-defined “parts list” of the PBN neuron subtypes that are the candidates to be performing these routing functions. Addressing this latter problem, we recently created a spatially-defined single neuron transcriptomic atlas of the PBN and in so doing discovered many transcriptionally unique PBN neuron subtypes (Nardone S et al., 2024). We are now using this information and the technologies mentioned above to : 1) determine the specific PBN neurons engaged and activated by the proximal satiety circuitries, 2) engineering marker gene-recombinase mice that will provide experimental access to these neurons, and then 3) using these marker gene-recombinase mice to determine the “higher” brain sites where these PBN “satiety” neurons project to ultimately cause satiety. These efforts, by allowing the hunger/satiety circuits to be followed as they traverse the previously opaque PBN routing hub, should clear the way for a neurobiological, mechanistic understanding of how hunger/satiety is regulated.

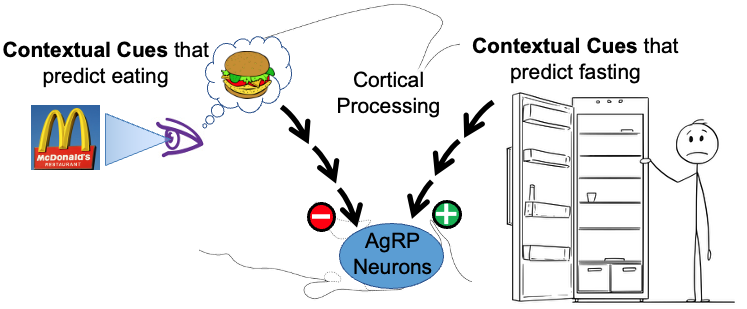

2. Rapid, feed-forward regulation of AgRP hunger neurons by cognitively-processed contextual cues – food-related cues inhibit while fasting-related cues activate AgRP neurons. Up until recently, it was thought that AgRP hunger neurons were controlled solely by feedback signals that reported the current status of the body’s fat stores. Unexpectedly, using real-time moment-to-moment monitoring of AgRP neuron activity in behaving mice, it was discovered that external environmental cues related to food (innate or learned), rapidly and potently inhibit AgRP neuron activity. Importantly, more recently we also discovered that contextual cues predicting lack of food do the opposite, and rapidly and potently activate AgRP neurons. It is now clear that, in addition to slow feedback regulation from the body’s fat stores, AgRP neurons are rapidly, potently and bidirectionally regulated by contextual cues from the environment. Given that the modern world is filled with a vast array of environmental contextual cues, and that the human brain has a remarkable capacity to learn associations with these cues, this recently discovered “feedforward regulation” by cortically-processed contextual cues is likely to have important implications for regulation of hunger/satiety. The goals of our studies are to determine the upstream neural circuits that mediate this regulation, and then use this information to establish the neural processes that are responsible as well as the purpose of the regulation.

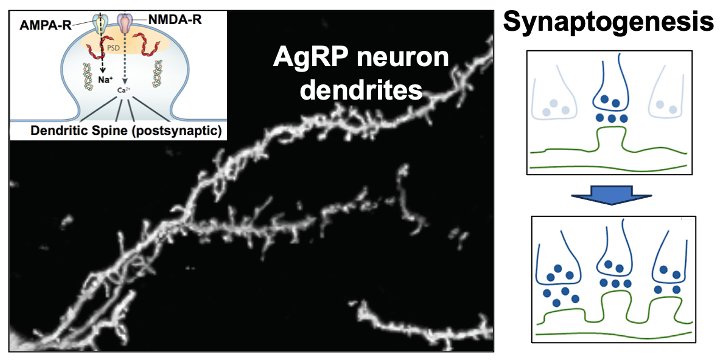

3. Synaptic plasticity in the excitatory inputs to AgRP hunger neurons. Excitatory (glutamatergic) input to AgRP neurons comes from the paraventricular hypothalamus (PVH) and this PVH (glutamate) —> AgRP neuron connection is responsible for the above-mentioned activation of AgRP neurons by contextual cues that predict the fasted state. Of interest, this PVH (glutamate) —> AgRP neuron circuit shows a remarkable degree of synaptic plasticity in that activation of this circuit creates new synapses on AgRP neuron dendrites. We are working to understand the molecular basis for this synaptogenesis plasticity as well as it’s role in regulating hunger.

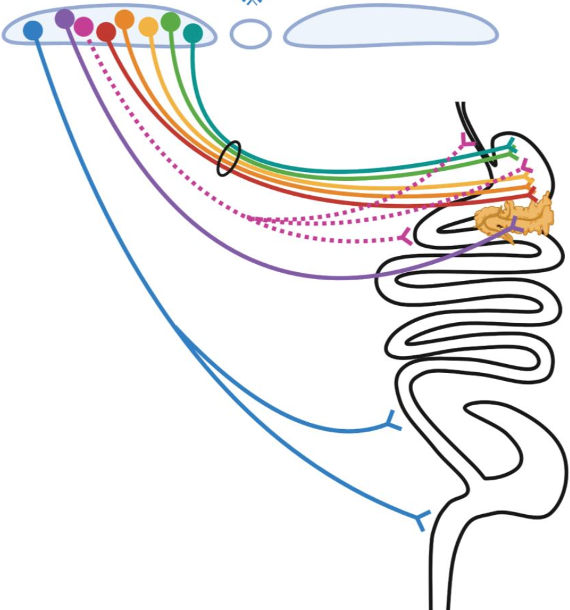

4. Highly-selective “labeled line-like” brain-to-gut communication by the parasympathetic nervous system. Parasympathetic control of gastrointestinal (GI) physiology, from distal esophagus to proximal colon, is carried out by preganglionic neurons located in the hindbrain dorsal motor nucleus of the vagus (DMV). DMV neurons do not directly cause GI responses, but instead they do so by synaptically engaging and activating downstream “postganglionic” enteric neurons (ENs) located within the gut which then release either acetylcholine (ACh) or nitric oxide (NO) and/or various neuropeptides to affect gut function. To account for the vast array of temporally-, spatially- and functionally-precise GI responses, it is widely believed that highly specific DMV-to-EN circuits (motor units) must exist, with their specificity being due to different DMV neurons projecting to different parts of the gut, and within a given part of the gut, different DMV neurons selectively targeting functionally distinct enteric neurons. Despite extensive evidence supporting the existence of such highly selective DMV-to-EN motor circuits, they are presently “hidden from view” and can’t be studied. This is because the means for uncovering and selectively manipulating them are lacking – and this is the case for all mammalian species. Our overall goal is to address this problem by leveraging the transcriptional diversity of DMV and EN neuron subtypes and the genetic tractability of a model organism (the mouse), to create the first-ever detailed roadmap of mammalian DMV neuron subtype to gut EN subtype communication.

GENETIC METHODOLOGIES USED BY THE LAB:

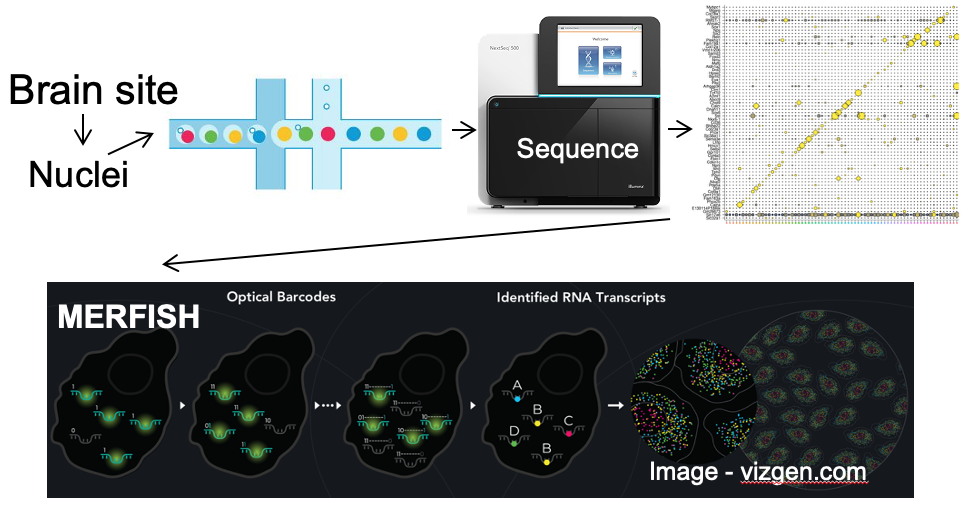

A. Single neuron transcriptomics and spatial transcriptomics:

a) to establish the neuronal “parts-list” for key nodes in the hunger/satiety circuitry.

b) to identify the marker genes that are used for neuron subtype-specific recombinase mice.

B. Generation and use of neuron subtype-specific recombinase mice which enable neuron subtype-specific expression of “tools”.